Madeleine Isenberg: The Rotter Relic

JGSLA Members Only Content: Member Articles

The following story appeared first in AVOTAYNU, Vol. XXVIII, No. 4, Winter 2012.

So Arnie, “Where did your Rotter family come from?” Having accumulated information from the Spis region of Slovakia, derived from reading thousands of tombstones and maintaining spreadsheets of birth, marriage and death records of people who once lived in the same area, I have become sort of a genealogist in reverse. I search for living descendants. Invariably, when I find someone whose name is similar to one on my lists, I just have to ask: “Where did your family come from? Did any of them once live in Slovakia?” Mostly, the answers are in the negative, but sometimes just initiating a conversation leads to historical discoveries I never would have imagined. Once I asked my cousin, the Chief Rabbi of England, Lord Jonathan Sacks, what he thinks about “coincidence versus beshert (predestination).” His immediate response was, “There’s no such thing as coincidence; it’s all beshert.” The following story of how I helped a family decimated by the Holocaust reconstruct its history seems to me to be beshert.

A friend, Arnold Rotter, told me that his ancestors did not come from Slovakia. Originally his father’s family lived in Poland, but they moved to The Hague, the capital of the Netherlands, sometime in the 1930s. When war reached Holland and they came under German rule, Arnie’s father and a friend decided to get away by riding their bicycles into France. They removed their yellow Jewish star arm- bands (which would have guaranteed instant death if caught by the Nazis) and successfully rode to France. From there, his father reached Switzerland and eventually the United States.

Arnie’s father always felt very guilty about leaving his family behind and preferred to talk with Arnie about his youth in the shtetl in Poland. He never discussed his life in The Hague, possibly, Arnie thought, because he felt guilty. Arnie, however, wanted to know more.

Thanks to the Internet, sometime in 2008, Arnie’s sister, Sharon, came across a little neighborhood newsletter in The Hague, Wijk Krant (dated December 2006), in which the editor, Jose Mendels, had included her interview with Frans Kagie, a non-Jewish man, regarding his childhood and reminiscences about Jewish life during World War II. More to the point, it was a memorial to Frans’ Jewish childhood friend, Mottic (Marcus) Rotter (1927-43), Arnie’s youngest uncle. Incredibly, this man in his 80s had carried the memories of the Rotter family with him for 60 years. The story was written in Dutch and needed to be translated into English.

The fact that the story existed was a small miracle in itself, but added to that was the rare publication of that newsletter on the Internet. The newsletter is just a local paper that is published every two months. That issue, out of a total of 60 in the last 10 years, was the only one ever put on the web and made available to the world! At the request of the Rotters, Jose Mendels, herself half-Jewish, provided a rough translation into English. After reading it, I felt I could improve the interview turning it into a first-person story and even added some explanatory notes. My version of Frans Kagie’s story follows:

Jewish Families of Scheldestraat, The Hague, Period 1937- 1945.

Dedicated to the Memory of Mottic (Markus) Rotter, 1927-1943It is 1937 and we are in The Hague’s River quarter, known as a neighborhood with lots of Jewish people, Orthodox and non-Orthodox, as well as Polish and Dutch; it is also known, of course, as Ward 7, the Red Light district. The threat of war is approaching rapidly. The fear of Nazi Germany is felt throughout the entire neighborhood, mostly among the Jewish people. The crisis is reaching its peak. Poverty, unemployment and hunger are everywhere. The welfare distribution for an unemployed married man with two children is 12.40 guilders net a week. Entire streets of rental apartments are up for rent and empty. Apartment owners offer special discounts; their apartments are fully painted and wallpapered and rent-free for several months.

No. 44 Scheldestraat was the home of the miserably poor Polish shoemaker, Mr. (Aron Yosef) Rotter, who walked with a limp, his wife and their three sons: Markus, Szulim (Shalom) and Samuel (Shmiel). The fourth son, Alexander, was able to flee in time to an uncle in the U.S. and was working there as an apprentice in the fur trade. Their youngest son, Mottic (Markus), was still attending the Jewish school on Bezemstraat. Mottic and I were best friends even though I was a Christian. Discrimination did not exist. We were both about 13 years old. After school, we boys would play football (soccer) in the streets or ping pong and card games in the back room at the Rotter’s home. Shmiel, the eldest son, also used this room as his fur workshop.

Later, when Mottic and I were a bit older, we started making hand muffs and mittens/gloves from very small pieces of left-over fur. One of us had to cut the fur carefully along the lines of a pattern, and the other had to sew it all together on a fur sewing machine. We would go out to sell our stuff together, but Mottic was clearly the better salesman. From the money we earned, we would buy food and candies.

Despite all the misery, the Sabbath was rather festive, if modest. After sunset on Fridays (Sabbath eve), the whole Rotter family would gather at the table, and I would be there too. The living room was furnished very simply and consisted only of a dining room table and some chairs, a coal-burning stove and a worn-out radio. Nevertheless, it was cozy. The Sabbath service was always led by Father Rotter. He would be at the right-hand side of the chimney, next to the Jewish candlesticks, and (for about 15 minutes) he would murmur Hebrew prayers and drink a small glass of wine. After the prayers, the simple meal of soup and latkes (potato pancakes) could begin. Afterwards, we boys would playa game of ping-pong or cards with some of our friends. Some of the friends I remember are Max van Vriesland and Harrie Davidson.

Early morning on Saturdays (Sabbath day), the Jewish men, boys and I would gather at the house of the Rotter family; from there we would start our leisurely walk to the synagogue on Wagenstraat. Some other men and boys would join us on the way through Pletterijstraat, Spui and Veerkade. Upon arrival at the synagogue, they gave me a yarmulke (skullcap), and I would enter with the rest. Since Jewish people were not allowed to touch money on the Sabbath, I had to come along to hand street musicians a dime or quarter on the way to the synagogue. After the service, the procession of men would take the same route back home.

On the Sabbath, Orthodox Jewish people also were not allowed to handle gas or electric instruments. I would run from one house to another to help with the gas and the lights. I would receive small gifts in thanks for my help. From the Alters (a textile salesman) at No. 40, I sometimes got a small piece of unsellable clothing, and yet I would be happy with that. Recognizing a particular loud call from someone in the neighborhood, I knew exactly where to go to assist with the gas or the electricity. In the summer of 1942, I had to check on the Wolf family at No. 131 to see whether they were still alive. No one answered the door, but I knew how to get in. The house on the first floor was totally deserted; it was very clean and tidy, the beds were made, and there were no dirty dishes in the kitchen. After the war in 1953, I met the two daughters by accident in The Hague; they had fled to Portugal with their parents in 1942 and had survived the war. Both had married in the meantime and lived in Canada and England, respectively.

There was an immense solidarity among the Jewish people. They tried to help one another whenever possible. One Sabbath night, the Alters asked me to check what food the Abrahamsen family with seven children at No. 119 had. Obviously, Mr. Abrahamsen knew why I was visiting, and he told me they did not have a lot to eat. When I reported back to the Alters, they gave me soup and other food for the family, which I had to deliver secretly yet in such a way that everyone could see it.

There was a small auxiliary synagogue on the corner of Zaanstraat and Dommelstraat where I also did a bit of cleaning on Fridays. I never knew what the purpose of that synagogue was.

Bram de Leeuw, brother of the butcher at No. 34, worked as a coal hauler at Fransen and Van Leeuwen coal business on Dommelstraat. He was a hard-working and very brave lad. One day in 1942 while loading coal onto a truck, he got into a fist fight with a couple of Germans and delivered a few solid blows. What followed was to be expected: we never saw brave Bram again.

In July 1943, all the Jewish people were told to bring a few personal belongings and await transport in front of their apartments. Pick-up trucks with open beds came and parked on the right-hand side in Scheldestraat. The Christian people were not allowed outside. The blacksmith and I watched it all from behind the curtains in the living room above the smithy on Dommelstraat. From an angle, we could see the Rotter’s house. The Germans forced the Jewish people to get onto the open trucks- men, women and the youngsters. The Jewish people helped each other. Father Rotter, elderly, handicapped and without his cane, was helped up by his sons. What a disgraceful scene it was to watch how thugs deported our neighbors and friends, in a criminal manner, to an unknown destination. Everyone thought they were being deported to some labor camp somewhere in Germany.

On the day before the arrest, Mottic and I had sewn some foodstuffs and candies into the lining of Mottic’s jacket. We boys also thought the Jewish people were being deported to a labor camp somewhere in Germany. The two of us put on a brave face, but we had a hard time saying our goodbyes. We shook hands; we couldn’t speak, and there were no words to express our feelings anyway. The atmosphere was very sad, but we put up a brave front. (Four days later Mottic lost his life in the gas chambers.)

Earlier, Father Rotter, handicapped as he was, had given me his silver-handled, black wood cane to look after until he returned. Until this day, I still have that cane. Weeks earlier, Shmiel’s fur working machine, models and financial records had been stored in the blacksmith’s workshop on Dommelstraat.

With the exception of Shmiel Rotter (born 1921) who survived the concentration camps, all the Jews from Scheldestraat were killed (gassed). Both Mottic and his mother were murdered in Sobibor on July 16, 1943, only four days after their arrest. After the war, in August 1945, Shmiel returned from Auschwitz, a living skeleton. He was very weak when he came to the blacksmith to pick up his belongings so, at his request, the blacksmith took his things to an address on Van Limburg Stirumstraat on a handcart. Soon after, Shmiel left for the United States where he joined his brother, Alexander.

Written September 23, 2004, revised April 27, 2006.

Frans Kagie

Additional Work

With the discovery in 2008 of this gem of a family history and Jewish life pre-World War II, as seen by an outsider, communication by e-mail and telephone began to fly among Arnie and his cousins, descendants of the surviving Rotter brothers. They wondered if this elderly man was still alive and if so, how could they contact him?

From Israel, Arnie’s cousin Joshua Salzberg contacted the Chabad rabbi in The Hague, Rabbi Shmuel Katzman, who helped to locate Mr. Kagie. Joshua tried to contact Kagie directly by telephone in August 2008. Since they could not understand each other’s languages, Rabbi Katzman suggested that editor Jose Mendels could help; she was asked to participate in a conference call to translate.

The family especially was intrigued to learn of the existence of the silver-handled cane, something that the hand of the grandfather they never knew had held and used for so many years. Was the cane still somewhere to be found? How would it feel for the hands of this generation to hold and con- template the ancestor who used to rely so heavily on it?

The newsletter also provided some other surprises for the family. For instance, regarding the reference to “Alexander,” Arnie commented, “Alexander might be a pseudonym for Bernard (Berle-Yissachar Dov) Rotter, the name probably was changed and the fictitious story of his going to America created to protect him from the Germans. (l never heard of this name in my interviews with my father about his childhood.) In fact, Bernard Rotter removed his yellow star and rode by bicycle thru Nazi-occupied Holland and Belgium to a cousin on a farm in France from where he was smuggled into Switzerland where he spent most of the war. Aside from this detail, the remainder of the basic facts sounds correct.”

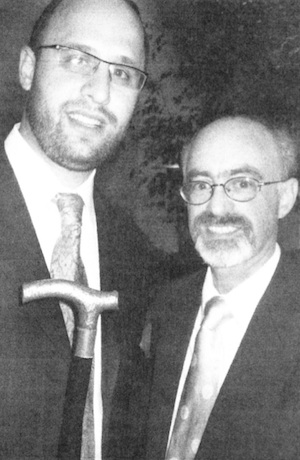

Baruch Salzberg (left) hands the cane of their grandfather, Aharon Yosef Rotter, to Arnie Rotter

As for the artifact itself, Arnie noted that it was a pity that neither his father nor uncle Shmiel got to see this article before they died He thought it noteworthy that “old man Rotter,” Aron Yozef and Myrel (Yiddish for Miriam) were only 45 when they were murdered in Auschwitz. No one had ever mentioned the limp to Arnie who speculated that Aron lozef may have been injured or had developed arthritis.

In another telephone call with Kagie – difficult because of the language barrier – they learned more about the family. As for the cane, he didn’t have it in hand, because it was in the house of his ex-wife who was on vacation. When she returned, he would retrieve and mail it to them right away- and indeed, he mailed the cane to Boruch Salzberg in Israel. Boruch brought it to the wedding of Yael Rotter in November 2008, in Israel. With great respect and honor, Boruch, the great-grandson of Aron Yozef Rotter, handed the cane to the father of the bride, Arnie Rotter. The cane was in frail condition and the handle came off. As an inanimate object, it didn’t need Arnie’s medical knowledge and expertise in radiology to determine where or how it was broken. They patched it together temporarily the best they could, but knew it would need some tender loving care to make it whole.

On his way back to Los Angeles, Arnie brought the cane to New York where he showed it to his cousins Claire and Margie and shared its provenance with them, at least as far back as their common grandfather, Aharon Yozef. Where and when it was made or how it was acquired are unanswerable questions. Eventually, Arnie brought the cane to Los Angeles where, with his wife Leah’s knowledge of skilled craftsmen, it was restored to a useable state, with the hope that no one would ever need to use it. Arnie ordered a special case to hold it.

Arnie became the curator of the cane, an heirloom and treasure, with more personal than monetary value. At any Shabbat meal, Friday night dinner or Shabbat lunch, as those seated around the table sing zemirot (Sabbath songs) with a joyous heart, Arnie gives a little wink to the cane, as if to say “Zaidy (grandpa), we are carrying on your legacy of Shabbat warmth, hospitality and zemirot. All is not lost.”

More to the Story

Arnie also e-mailed me the last letter written by his namesake, his grandfather Aharon Yosef Rotter, to Beliie (Arnie’s father known as Bernard or Beryl, or as Arnie learned from Hagie’s account, Alexander). It was written in German one week after the arrest on September 19, 1943, from Westerbork, the Dutch transit camp for Auschwitz:

Westerbork 19.9.43

Dear Bertie,You will be happy to hear from us again. I, Schmiel and Szulim are here. Tanle (Auntie) and Mottik have gone to Uncle David. How are you? Everything is fine by us. We are, thank God, all healthy. Have you already been in con- tact with Uncle Harry? It is very surprising to us that we still have not received the certificaatnumer (certificate number) from Eretz. I hope that you will still be interested in (doing?) that. We have heard from Beppie that you received the package. We were very happy, as you can imagine. We are here with many acquaintances, Turin, Sack, Oskar, Frojim, Findling, Sonnenberg and many others. Mrs. Swarz also is here. From Jean we have not heard anything.

So, dear Bertie, I hope that you will answer soon, and also won’t forget the certificate number. Regards and kisses from all ofus. Also send regards to Uncle Harry.

A. J. Rotter

Amie surmised that the certificaatnumer was a visa to allow his family to emigrate and escape from the Germans. The Uncle Harry in America, indeed, was the relative who, after the war, sponsored Arnie’s father to come to the United States. According to the dates provided by Kagie, Aharon Yosef was murdered just five days after the date of the letter. By the time Bertie received it, all of his family was dead.

At this point, I began to wonder if I might help Arnie learn more about this branch of his family, and I asked if he had any more information. “From where in Poland had they come? Did he have any photographs?” In response, Arnie e-mailed the only known family photograph and supplied the following data:

- Bernard (Yissachar Dov) born in Grodzisko

- Aharon Yosef (owner of cane), born Dynow/Brzozow or Dinev

- Michoel, born Dobromyl near Przemashil, Galicia, now Ukraine

- Myril Brod, born Grodzikso

Armed with this information, I turned first to Jewish Records Indexing-Poland <www.jri-poland.org> an invaluable first resource for Polish research. Although I could not find either Arnie’s great-grandfather or grandfather, I did find some Rotters from Dobrimil who were perhaps relatives. I noted that a Shmuel Rotter was married to ltte/Jutte. The next stop was JewishGen’s Family Finder <www.jewishgen.org/jgff> where I found 31 researchers looking for someone named Rotter, but just one, identified only by a number, for a Rotter from Dobrimil or Dynow. This seemed promising so I sent a message of inquiry.

Finally, since this entire story is about a family murdered in the Holocaust (with a few survivors), the Yad Vashem Central Database of Names <http://db.yadvashem.org/names/search.html?language=en> was the next stop to see if it had anything for an Aron Rotter. I found a Page of Testimony for Myrl Brod Rotter, born June 8, 1888, in Grodzisko, Poland. Three records exist for Aron Josef, born December 16, 1898, in Dynow and one for Markus/Mottik, also born in Grodzisko.

At the same time, Arnie’s sister Sharon made her own discovery as noted in the following letter:

Arnie and all,

Many thanks to Madeleine Isenberg for the time and ef- fort she obviously dedicated to arranging the information we have. Slowly but surely, the details of our family are being flushed out and developed into a realistic story. Now if everyone is sitting down, I thought I’d let you know what the latest little search online has dug up. Perhaps it will explain something that was mentioned in the letter from Aron Josef that Amie had translated .

I did another quick search on Aron Josef Rotter on Google, and lo and behold, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has online a digital photograph of a certificate with the photos of our grandparents, Aron Josef and Myrel Rotter! I am including the link.

It seems that a Salvadoran citizenship cel1ificate was issued to them and a copy sent to Westerbork, too late to help them sadly, by George Mandel-Montello. He worked from Switzerland, opening an office in conjunction with a number of Jewish organizations attempting to save as many Jews as possible. This certificate was probably in the batch of 1,000 originals that were donated to the museum by Mandel-Montello’s son.

I wonder if this was the certificate that was referred to in the letter, and even further, if our father, Berel, was involved in Switzerland in arranging the papers with Mandel-Montello’s office (perhaps through some Jewish organization). Arnie, do you have any details about the date that Daddy arrived in Switzerland and where he lived? We know that he stayed in a hotel-like refugee camp with many other Jews (including the Satmar Rav at one point), so maybe he was able to speak to people who had connections to the Salvadoran operation.

The fact that we can find such incredibly pertinent and exciting information about them from a simple online search makes me wonder how much more we can discover with a little extra effort.

Love to all, Sharon and family

Another surprise anived the same day as Sharon’s letter, a message from the unknown researcher on the JewishGen Family Finder:

Thank you for helping me find my relatives. My name is Chaim Mechel Cohen. I am named Mechel after my great-grandfather, Mechel Rotter of Dynow. My mother, Roiza Cohen, is a daughter of Moshe Berger and Baila Nesha, a daughter of Yechiel Mechel Rotter and his wife, Perl Tauba. They had a son Aharon Yosef married to Brad family of Gradzisk and had two children, Shmiel and Berl. I would like to know their children and grandchildren. They also had a daughter, Esther Adler, who had three daughters. I would like to know about them too. The Zaida Mechel was born in Dobromil to his father Shmuel and his mother Yitta. He married Perl Tauba daughter of Shulim Shochna and Yenta Berger.

Arnie communicated immediately with Chaim and discov- ered that Arnie’s parents had attended Chaim’s wedding! Amie wrote, “After speaking with my cousin Chaim Mechel Cohen, I now know that my full Hebrew name (paternal side) is Aharon Yosef ben Yissachar Dov ben Aharon Yosef ben Yechiel Mechal ben Shmuel.”

Conclusion

While I have been doing genealogy research, mostly for my own family, for more than 20 years, I also have begun writing stories to make family history more understandable to the younger generations. I have discovered that everyone has a story and this one was so compelling I just had to write it down for them. I probed for more information and was able to discover more. I felt I had helped Arnie’s family bond tighter in sharing their discoveries and heritage. They may not have had the time or inclination, but I could start it for them. As you can see, one little step led to another, until it resulted in lots of beshert findings. I get my satisfaction in knowing I facilitated that effort.

Madeleine Isenberg is a retired computer programmer/technical writer and self-styled “Stelaeglyphologist,” decipherer and translator of thousands of tombstones. She coauthored Jews in the Spis Region, Vol. I, Kezmarok and Its Surroundings, with colleague Mikulas Liptak. Isenberg lectures about tombstones and beginning genealogy, has created two KehilaLinks websites, translates for JewishGen’s Yizkor Book Project and contributes to JOWBR.