by Abraham Hoffman

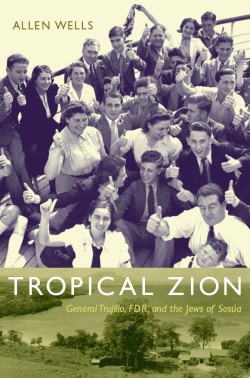

TROPICAL ZION: GENERAL TRUJILLO, FDR, AND THE JEWS OF SOSUA

by Allen Wells

Durham: Duke University Press, 2009.

448 p. Map, Illustrations, Notes, Bibliography, Index.

Buy this book from Amazon

At first inspection this book might seem to be a major examination of a minor event. After all, fewer than a thousand German and Austrian Jews were rescued in General Rafael Trujillo’s scheme to bring Jewish refugees to the Dominican Republic. Allen Wells, professor of history at Bowdoin College, demonstrates that while the numbers seem insignificant in terms of the Holocaust, Trujillo’s invitation stands out as the lone example of rescue offered by the free nations in the years immediately preceding the start of the Second World War.

Trujillo’s offer came out of the Evian Conference of 1938, a meeting called by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in response to criticisms of United States refugee policy. Doomed from the start, the conference seemed to consist of one delegate after another stating his nation had no room for Jewish refugees. In retrospect this should not surprise anyone; Latin American nations were notoriously anti-Semitic, European countries (not yet invaded by Hitler’s Germany) claimed to have no room for refugees, and the United States State Department, infested with anti-Semitic bureaucrats, strictly enforced restrictive quota laws.

Amidst all the speechifying and hand-wringing, Trujillo’s offer stood out. Trujillo was willing to take in not just a few Jews but up to a hundred thousand Jewish refugees. He would settle them in agricultural colonies, away from the prejudice and danger of Nazi Germany and Austria. To be sure, Trujillo was no altruist. He had his own motives for taking in Jewish refugees. At the top of the list was the need to remake his international image as a brutal dictator and tum him into a humanitarian. This desire stemmed from the massacre of 15,000 Haitians living in the Dominican Republic in 1937. To shake off the criticism surrounding this atrocity, Trujillo saw opportunities in rescuing Jewish refugees.

Another motive was racist. Unlike Hitler, Trujillo saw the Austrian and German Jews as white people, and he wanted white immigrants to come to his nation and help make it more Caucasian. To this day Dominicans reject any evidence of African ancestry and consider mixed-blood ancestry as mestizo (white and Indian) even though the Indians on the island were killed off centuries before the Dominican Republic became an independent nation. To facilitate Jewish immigration, the Dominican Republic Settlement Association (DORSA) was created to screen applicants and settle them at Sosúa, an agricultural settlement on the nation’s north coast.

Wells devotes the major part of his book to the challenges the refugees faced. Trujillo wanted young men and women with agricultural backgrounds; but most of the German and Austrian Jews were urban professionals, and some were older, not younger people. Although Sosúa was a beautiful area, with an expansive view of the beaches and ocean, much of it was not suitable for agriculture. Jews had to learn to be farmers, and what they tried to grow became a process of trial and error. Eventually the colony found its greatest profit in the dairy industry, producing milk, butter, and cheese of high quality. Jews also had to face learning another language, the shock of leaving a familiar culture for an alien one, and the constant need of financial assistance to make the colony viable. Money came from the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Dedicated supporters of the colony such as James Rosenberg and James Rosen were instrumental in making the colony succeed. However, some Jews found the work too taxing under tropical heat and humidity.

Sosúa was less an Eden than a place of contention. When the war broke out, the possibility of rescuing large numbers of Jews ended. After the war only a few hundred people remained at Sosúa, as many left the colony 2 for the United States (its immigration restrictions were relaxed in the postwar period), Israel, and other nations.

Wells’s book seems about as definitive as one can make it (there have been previous studies), and he offers the view of both an academic scholar and as the son of one of the Sosúa refugees who left the Dominican Republic after the war. He interviewed dozens of former colonists as well as some of those who stayed in the colony, and he brings the story up to the present day. No longer isolated from the rest of the island, Sosúa has become a minor tourist resort, and among the visitors are former residents and their children who are alive today because a dictator aspired to a more positive public image for himself.